Museum

Introduction

In 1932, the content of Gibran's studio in New York, including his furniture, his personal belongings, his private library, his manuscripts and 440 original paintings, was transferred to his native town Bsharreh. Today, these items form the content of the Gibran museum.

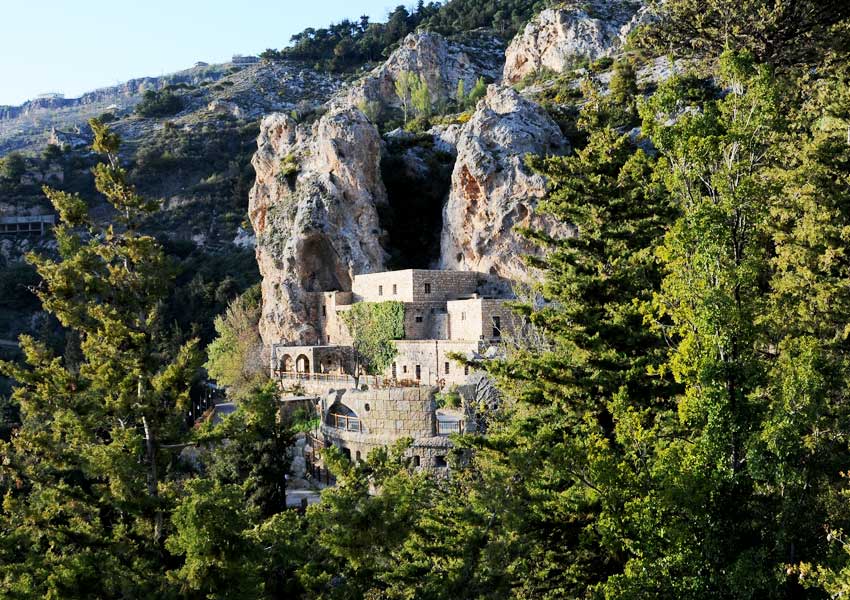

Originally, a grotto for monks seeking shelter in the 7th century, the Mar Sarkis (Saint Sergious) hermitage, became Gibran Khalil Gibran's tomb, and was later turned into his museum.

By the end of the 17th century, Carmelite monks living in the Qadisha valley, the sacred valley, began construction of a new monastery, which was completed in 1862.

more

In the 7th century, Saint Sarkis’s cult reached northern Lebanon. At the foot of the mountain, overlooking the Valley of the Saints, close to the Phoenician Tomb, east of the existing building and amidst the Caverns of the Hermits, lies the cave that Gibran chose to be his tomb (room XII).

It was known as the Hermitage of Saint Sarkis.

In the 15th century, a small building was erected east of the hermitage as a residence for the Papal Nuncio. At the time of the famous Mokaddam Rizkallah (1472), the building was inhabited by the Flemish Fragrifon and the missionary Francis of Barcelona. The cavern became the core of a church.

The events of the novel of the Monk of the Qods Lake, by the late Jesuit Father Henri Lammens, are closely linked to this place, to these times and to the Mokaddam Rizkallah.

By the middle of the 16th century, the relations between the Maronites of Mount Lebanon and France were so cordial that the small building was converted into a summer residence for the French Consul.

In 1633, at the time of Patriarch Youhanna Makhlouf, a group of Carmelite Monks came to the region and occupied one of the hermitages belonging to the Saint Elisha monastery in the valley of Qannubin. These Monks were followed by Father John the Carmelite, who acted as a liaison between the Pope and Patriarch Girgis Sibaali. In 1699, these Monks were joined by Friar Jeronimo from Mount Carmel who was a polyglot, proficient in Arabic and in many field of knowledge.

In consideration of the great culture of the Friar and of his organizing the proselytism of the region, and in gratitude to the Monks for their activity in the fields of health care and religious education, the notables of Bshareh offered them the hermitage, the existing building and the surrounding oak forest, as a mortmain property, in order to pursue their missionary activity and promote spiritual culture in the region lying between Wadi Qadisha and the cedars.

In1701, the Monks demolished the existing building and replaced it, to the east of the hermitage by the monastery which is still standing. In 1908, some of the Monks moved down to Bsharreh and built the Saint Joseph Monastery which is still known as the "Monastery of the Carmelite Fathers”. The rest of the Monks remained in the old monastery.

From 1701 until 1908, the Monks were diligently active in their religious, social and educational activities. They also cultivated the land adjacent to the monastery and irrigated their crops from basins which were still existent not so long ago. They also progressively enlarged the monastery.

According to the Annals of the Monks and popular traditions, one of them, Friar Michael, became famous as an example in piety and hard work - "for fear of the devil", he said. Gibran often spoke of him to Mary Haskell. It was he who excavated the galleries and carved the steps in the rock that lead to the hermitage which, by then, had become a church, and was visited by worshippers on Sundays and feast days.

On the western side of the "Small Chapel" (the upper room), Friar Michael pierced a long tunnel through the mountain until he reached the cliff facing the city, where he erected small campaniles whose bells ring for prayer.

The Annals of the Monks tell us also that Our Lady of Lourdes, pitying the suffering Friar Michael who had to carry water to irrigate his crops, appeared to him one night and beckoned him to follow her to a nearby rock east of the monastery and signaled to him to dig beneath it. He did, and a fountain sprang out. The place was consecrated to Our Lady of Lourdes. It is now a sanctuary visited by worshippers. It was enlarged and illuminated by the Gibran National Committee when it restored the monastery and turned it into the Gibran Museum.

In 1926, while in New York, Gibran decided to buy the monastery for his retirement and the hermitage as his final resting place. Upon his request, his sister Mariana purchased both the monastery and the hermitage. On the 22nd of August 1931, Gibran's mortal remains reached Bsharreh. The transformation of the new monastery into a museum did not occur until 1975 when the Gibran National Committee restored the monastery and built a new wing in the eastern side. The floors of the museum were linked through an internal staircase to create a harmonious space where the works of Gibran are to be exposed.

more

In his last will, Gibran bequeathed all his works and his studio furniture to Mary Haskell, leaving for her to decide whether to accept them as a token of gratitude or to bequeath them to his native town Bsharreh. Remembering his nostalgia for his hometown Mary fulfilled what she knew was his desire.

During the next two years, 1931-1932, the treasures found in Gibran’s studio were freely tossed about. But the combined efforts of Mary Haskell, the Gibran Youth Committee and Gibran’s Lebanese friends, Gibran’s legacy was shipped from his studio in New York to Bsharreh.

Afterward, the Gibran National Committee was founded. His paintings were exhibited in many places in Bsharreh. But from the election of the first Committee until the 1971 election, the constant concern was to create a suitable museum to receive the paintings of Gibran. Many schemes and architectural designs were presented.

A settlement was finally attained by Members and Director Farid Salman of the Gibran National Committee in 1971 when they decided to convert the monastery into a museum. Throughout 1973-1975, the monastery slowly began to take the shape required by Gibran’s idea of seclusion.

An annex, joining the basement to the upper storey, was added to the existing building.

The walls were purposely kept rough to the rough-hewn aiming to create a harmony between them and the paintings backgrounds. Tunes for the flute were chosen among dozens of entries. They are played by Farid Fakhry, who, in his own words, offered them as a gift to the spirit of my brother Gibran.

And the monastery was finally transformed into Gibran Museum to embrace with its sixteen halls his masterpieces, manuscripts, personal library, archives and furniture including his bed and his easel, brought back from his apartment in New York. His address appears on one of his leather briefcases (room III).

From Hall XVI, seven steps lead down to the ancient hermitage where Gibran now rests in the heart of the rock halfway between the Holy Qadisha Valley and the Cedars of Lebanon.

All the masterpieces are exhibited in the 12 rooms of the three floors of the Museum, leading at the end to Gibran's tomb. The rooms are all numbered with roman numbers, firebrand on cedar wood tablets.

Giban's resting place is separated from room XVI by seven stone steps carved in the rock of the monastery. The old hermitage is the cemetery.

To the west side is another collection of some of Gibran's personal belongings and furniture: his painting corner, small casesand boxes, a short bed, a table witness of the artist's sleepless nights spent in company of words, a chair... They all remind us of Gibran's New York studio.

Towards the north side, we can read the epitaph that Gibran wished to be written on his tomb. Through the cracks of the piece of wood appear parts of the coffin.

Then going eastward, we see in a cornet two chandeliers and a portrait of Gibran painted by his friend Youssef Hoayeck, when they were in Paris.

Getting to the exit is a portrait of Gibran painted by the Lebanese artist Cezar Gemayel.

In 1995, the museum was further enlarged and supplied with up-to-date equipments enabling it to exhibit the entire collection of Gibran's manuscript, drawings and paintings.

A plan for the whole site including extensions, a parking and an access road was executed in the summer of 2003 with the aim of preserving this part of the Lebanese heritage molded into a privileged cultural and touristic site.